Paul and the Citizen Body (2021)

Published in English.

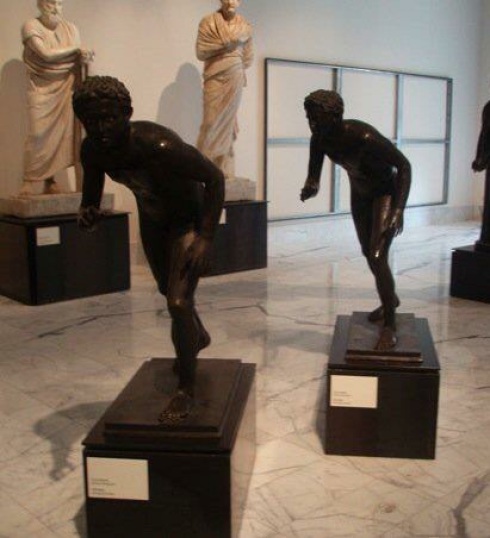

In this study, Janelle Peters argues Paul's construction of an individual body and communal body in 1 Corinthians serves as an alternative to Roman and Greek models of citizenship. She situates the

athletics and veiling of 1 Corinthians within ancient authority and citizenship, which prioritized having control over one's body and head. Contrary to scholarly assumptions that these citizenship

indicators would have restricted the previous freedom of all women in order to present conformity with Roman norms, the author contends that the elements of bodily control Paul imposes on the

Christian body construct a new citizen body that appeals to Roman and Greek notions of prestige in order to transform the experience of the Christian both in the present world and in the heavenly

politeuma. Unlike civic honors within Roman and Greek secular polities, this citizen body is accessible to all, regardless of social status.